Ann Curthoys, Catherine Kevin and Zora Simic

Since at least 2015 in Australia, domestic violence has been a highly visible issue when bereaved survivor of domestic violence, Rosie Batty, was appointed Australian of the Year, and the Royal Commission into Family Violence in the state of Victoria was launched. The Commission’s March 2016 report recommended a multi-faceted approach which prioritises advocating for cultural change around violence. Historical understanding is an essential facet of this cultural change.

We are three historians researching the first national history of domestic violence against women. We begin our project in the mid-nineteenth century when marital cruelty began to feature in changes to separation and divorce laws across the Australian colonies (starting with South Australia in 1857) and we will end with the current ‘shadow pandemic’.

As the feminist historians who first opened up this topic to historical investigation in the 1980s recognised, the prevalence of domestic and family violence is impossible to quantify in both the past and the present given it’s a mostly behind closed doors phenomenon and associated with shame and secrecy.

Silences haunt histories of gendered violence. Yet what is striking is that across the 170-year-period, the most common form of domestic violence – men’s violence against their female partners – has always been visible in some form, including in public discussion about whether it was (and is) a peculiarly ‘national disgrace’.

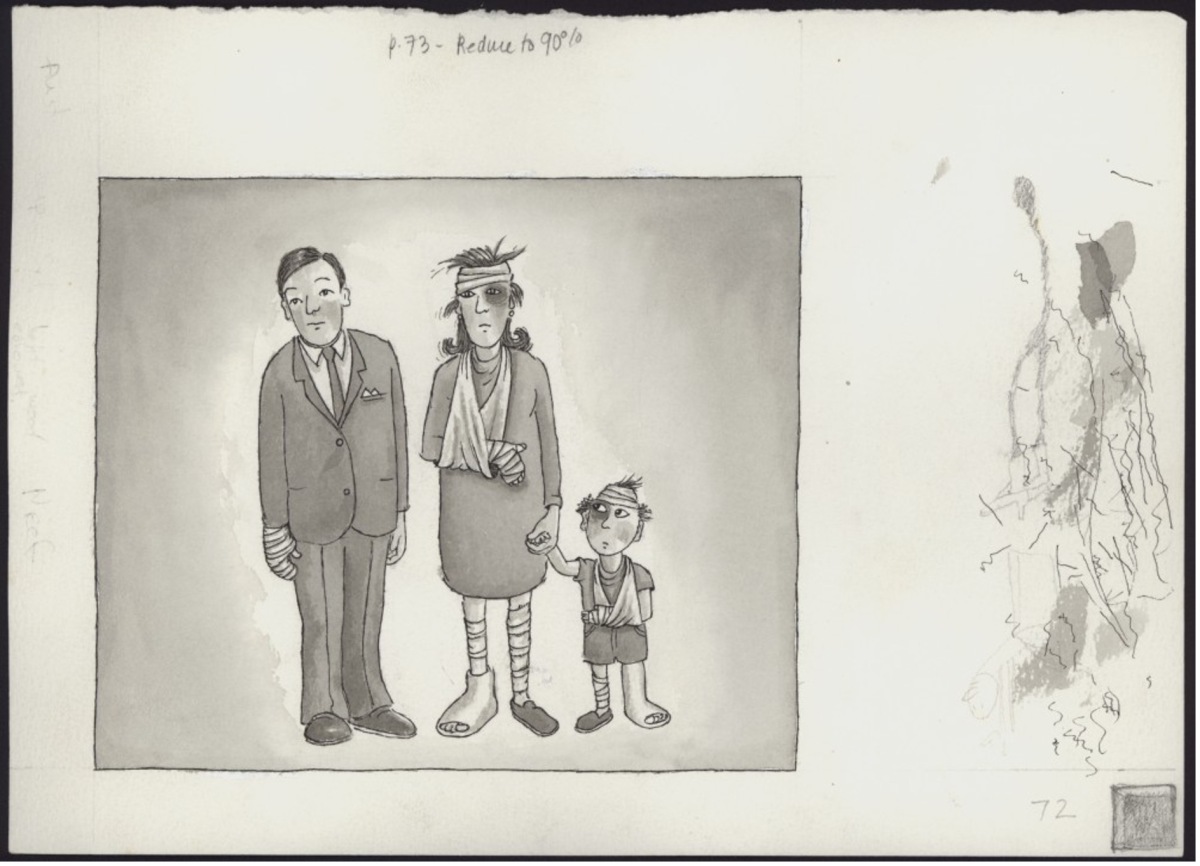

In the nineteenth-century, the widely used terms ‘wife-beater’ and ‘wife-beating’ placed the stress on the ‘blow’ or the ‘wallop’, and the excessive drinking of the assumed working-class perpetrator or ‘husband’. Sometimes there was recognition that violence could occur in more ‘respectable’ families, and commentators pondered whether ‘wife abuse’ was more rampant in the colonies, or whether, as one 1870 editorial declared, that it was a ‘scandal to all English lands’.

Men wrote about other men under the auspices of condemning ‘wife-beating’ as an uncivilised practice, and a taint on any colonizing and civilising claims – but with scant recognition of the violence of colonialism itself, including against Indigenous women.

The terms ‘wife-beating’ and ‘wife-beater’ remained in common usage well into the twentieth-century, maintaining an emphasis on physical violence and the stereotypical ‘wife-beater’, a category which by the post-war period included the ‘migrant wife-beater’. But for some recently arrived migrants from Europe, ‘wife-beating’ appeared distinctively common in Australia – as one German woman told a reporter in 1953, ‘I am often surprised by what Australian women have to bear’.

In Australia, as in the UK and elsewhere, it was women who had experienced gendered violence who brought it to the attention of the Women’s Liberation movement in the early 1970s. Australian feminists were amongst the first to develop the term ‘domestic violence’, inaugurating an enormously generative cultural shift in comprehending its causes, prevalence and features, as well as an entire sector dedicated to addressing it. Yet from its inception, ‘domestic violence’ has been an evolving and contested term, including among feminists. At the first national conference on domestic violence in 1985, refuge worker Dawn Rowan referred to the ‘Criminal assault of women in their homes (euphemistically called domestic violence)’, while Vivien Johnson lamented that the ‘spurious neutrality of “domestic violence”’ distanced the issue and avoided the critique of marriage contained in ‘wife bashing.’

Another speaker at the 1985 Conference, Beverley Ridgeway, represented the ‘Aboriginal women’s viewpoint’. She argued that while on the surface, domestic violence within the Aboriginal community appeared to ‘resemble that within the non-Aboriginal community’, it could not be interpreted or responded to in the same way. As it was an issue, she argued, ‘which traditionally did not exist we can only assume it was another destructive element perpetrated on us by the non-Aboriginal community’. The support she sought was assistance to reduce domestic violence in a ‘manner which is appropriate to us.’ By the 1990s, a clear preference emerged within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities for the term ‘family violence’, encompassing that it does extend family and kinship relations.

For decades now, various data has shown that First Nations women experience family violence at alarmingly higher rates than average.

For at least as long, Indigenous women have drawn attention to the extent of the problem and offered powerful intersectional analyses concerning the consequences of colonisation and the intergenerational trauma that has resulted.

As a recent open letter by Associate Professor Hannah McGlade, Professor Bronwyn Carlson, and Dr Marlene Longbottom made clear, the lack of outrage about the victimisation of Aboriginal women and children signals the ongoing normalisation of this violence. In current discussions surrounding the development of a new National Plan to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children, First Nations women have called for their own separate National Plan, led by them, as opposed to being included as ‘afterthoughts’ in processes which have thus far failed to deliver.

Australia now faces a paradox that while there has been a significant increase in public awareness of and scholarly knowledge about domestic violence, there has been no reduction in the rates of domestic, family, and sexual violence, even while overall rates of violence have fallen. One of our central tasks as historians is to help account for this situation by taking a long view. We need to understand the significant changes over time in public discourse, legal frameworks, and activism to combat domestic violence as well as just how and why domestic violence has wreaked such enormous damage on women, children, and the society as a whole from the 19th century to the present.

Authors’ Bios

Professor Ann Curthoys (Sydney University) has researched, taught, and published on many aspects of Australian history, and also on questions of feminism, cultural studies, and historical writing and theory. Associate Professor Catherine Kevin (Flinders University) teaches and researches in the fields of Australian history and feminist history, particularly Indigenous-settler relations, the politics and experience of the reproductive body and gendered violence. Dr Zora Simic (UNSW) teaches and researches past and present feminisms, especially but not only Australian; twentieth century Australian history, especially gender history and migration history; and histories of sexuality. This research is part of 2021-2024: ARC Special Research Initiative (SRI) SR200200460, ‘A History of Domestic Violence in Australia, 1850-2020’