Karen Boyle is a professor at a striking UK university. This blog was submitted on 21st November.

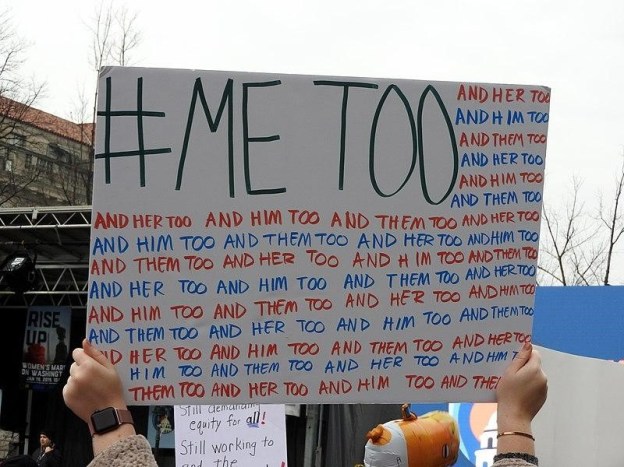

‘ME TOO and her too and them too and him too’ by Cyndy Sims Parr and used under a Creative Commons licence

On 15 October 2017, actress Alyssa Milano tweeted:

Me Too.

Suggested by a friend: “If all the women who have been sexually harassed or assaulted wrote “Me Too” as a status, we might give people a sense of the magnitude of the problem.

(@AlyssaMilano, 15 October, 2017)

Within 24 hours, 12 million Facebook posts using the hashtag were written or shared; within 48 hours, the hashtag had been shared nearly a million times on Twitter.

In some ways, #MeToo exemplified the feminist possibilities of social media: each new post joined an existing conversation and allowed us to build a picture of what they had in common. This was not a million miles away from the consciousness-raising groups of the Women’s Liberation Movement, where women shared their experiences – including of sexual violence – in order to build an analysis of what they shared in a patriarchal society. But, where consciousness-raising typically took place in small, closed groups, #MeToo brought with it a more politically diverse and potentially global audience.

However, I want to sound a note of caution about the way #MeToo is now increasingly referred to as a movement. To do this, I want to think about the relationship between #MeToo as a hashtag and Tarana Burke’s Me Too, founded in 2006. Burke founded the Me Too movement in response to a young woman’s disclosure of sexual abuse. At the time, Burke shut the young woman’s testimony down as quickly as she could. Yet, part of the reason for Burke’s reluctance was that the young woman’s testimony echoed her own experiences. For Burke, Me Too was (and is) about the pain and difficulty of recognition and solidarity, and the work this knowledge demands of us.

When Milano tweeted #MeToo, she was not aware of Burke’s work. After the tweet went viral, Burke’s work was publicly acknowledged, following a by now well-established pattern of Black feminist mobilisation online. However, Burke notes that the mainstream acknowledgement has been limited:

While it’s true that I have been widely recognized as the “founder” of the movement – there is virtually no mention of my leadership. Like I just discovered something 12 years ago and in 2017 it suddenly gained value. #metooMVMT #metoo

(@TaranaBurke, 21 February 2018)

Burke has consistently differentiated between the act of speaking out and the work that must follow on from that acknowledgement of personal experience in order to effect change. The media emphasis on Burke-as-founder obscures this, not least by emphasising her own personal story as a survivor.

In my research on the media coverage of the Harvey Weinstein case, I have similarly found that the decades of feminist activism and research on sexual harassment and abuse preceding October 2017 have largely been ignored. Not only have spokespeople for organisations like Burke’s been largely missing from mainstream accounts, where feminism has featured it has too often been as a site of suspicion because of the (in)actions of prominent, individual feminists.

What I want to emphasise, then, is the importance of understanding #MeToo not only as a social media trend, but as a mainstream news story. #MeToo was a response to a mainstream news story with Hollywood at its centre, so it is hardly surprising that #MeToo in turn became a major news story for global media outlets. Equally unsurprising has been the emphasis placed on the experiences of economically and racially privileged US women in this coverage. But this is a critique of the media, not of a movement, or even of the individuals using the hashtag on social media.

Louise Armstrong, who has written about media coverage of child sexual abuse testimony, argues that for the media “the personal is the personal” – and this can stop us seeing the bigger picture. There is also the risk that it makes stories about violence the stories only of the victim/survivors, as though the perpetrators somehow had nothing to do with it.

Even in the #MeToo era, men in public life have not been routinely asked if they perpetrated sexual violence, though after #MeToo went viral, there was a period where women in the public eye were almost routinely asked in interviews if they had a #MeToo story. This relentless focus on personal trauma compromised victim/survivors’ abilities to choose whether/how to tell their own stories, but also downplayed the expertise amassed by feminist organisations and researchers who have been listening to survivors for decades.

The feminist slogan “the personal is political” doesn’t mean that telling personal stories publicly is always or necessarily politically progressive – nor does it place an obligation on survivors to speak out. Unlike the women in consciousness-raising groups, those sharing #MeToo on social media since autumn 2017 haven’t necessarily had very much else in common, including how they make sense of their experiences of sexual harassment and abuse. This is only surprising if we think of victim/survivors as a homogenous group.

Of course, some women (and men) have been galvanised to political action by #MeToo, but a diverse group of people posting #MeToo do not necessarily constitute a movement. A movement, as Tarana Burke says, is work. Emotional work is part of this, but not all of it: the work this generates then includes advocacy, support, campaigning, policy development, research. This work takes time, and can be obscured by a focus on one-off statements.

For all of these reasons, I refer to #MeToo as a moment rather than a movement. As the women of the Tufnell Park Women’s Liberation Workshop wrote in the inaugural edition of Shrew in 1970:

We can be so written about and give so many interviews that we can be deceived into thinking that there is a movement when all we’re doing is dealing with the press and TV. (Tufnell Park Women’s Liberation Workshop 1970: 4)

Of course, dealing with the press and TV matter. But we should not allow the media to define our movements to end men’s sexual harassment and abuse of women.

Karen Boyle is Professor of Feminist Media Studies at the University of Strathclyde (@Unistrathclyde) in Glasgow, Scotland. She is the author of #MeToo, Weinstein and Feminism (Palgrave, 2019) and Director of Strathclyde’s Applied Gender Studies programme.

“

“