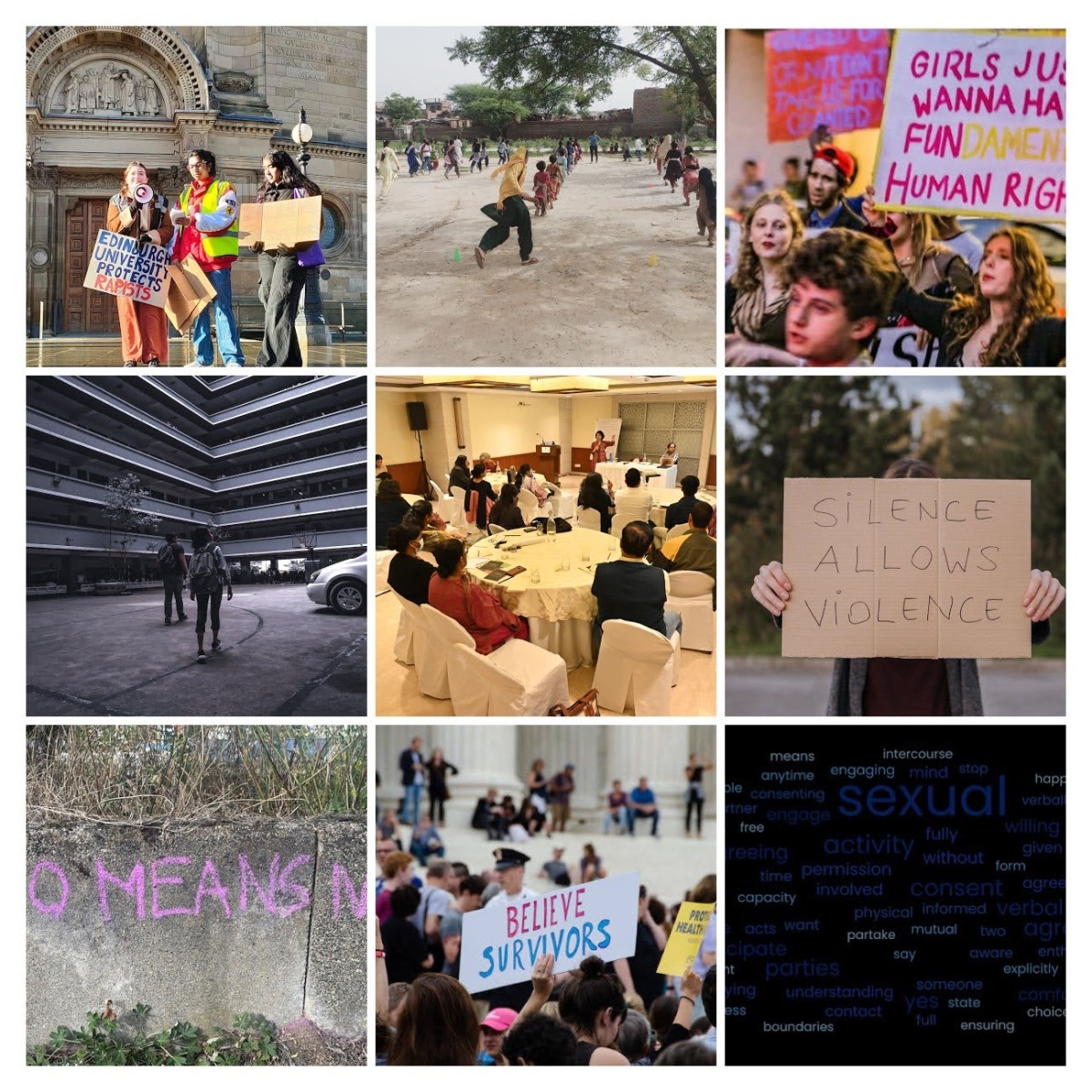

We’ve come to an end of our annual 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence Blogathon, running between the International Day to End Violence Against Women and International Human Rights Day today. Our blogathon this year focused on the theme of sexual harassment and sexual violence in higher education institutions and is a continued collaboration between GENDER.ED at the University of Edinburgh, the Gendered Violence Research Network at the University of New South Wales and the Centre for Publishing at Dr B R Ambedkar University Delhi. This year we were joined by guest curators from Margherita von Brentano Center at Freie Universität Berlin, for the Una Europa Gender Equality Network (UGEN). Our blogathon brought together voices from research, student activism, and institutional perspectives to raise awareness of the #16DaysofActivism Against Gender Based Violence global campaign.

While our annual blogathons typically span transnational contexts, this year we chose to focus on the country-specific and institutionally-distinct contexts that our curators were writing from. Our introductory blog historicised demands for institutional change from Australia, the UK, and India, with our curators noting how campus screenings of the documentary The Hunting Ground acted as a catalyst spurring action around addressing sexual violence. Landmark national surveys were undertaken in Australia, and the question of sexual violence was understood as one that affects staff and students. In the UK, similar surveys found a widespread culture of toxic masculinity prompting the question of what relationship University systems had with wider criminal justice procedures. Student activism has shifted the calculations that Universities make so that it is now seen as institutionally risky and disreputable to be seen as not acting. In India, institutions have responded in the context of wider conversations around sexual violence, government committees, and feminist activism around gender-based violence.

This year we curated our blogs to move through three stages: an interrogation of concepts; the process of addressing violence prevalent in institutional settings; and the challenges and registers of institutional activism.

We began with asking what kind of concept violence is. Drawing on her work on domestic abuse, Catherine Donovan wrote about a “public story” of violence that “doesn’t just describe a problem, it creates a problem with particular contours in our minds.” Donovan suggests we think about violence as it emerges through structures of power and “relationship rules” that need to be unhooked from their cis-gendered and heterosexist binaries. Ngozi Anyadike-Danes wrote next on the tricky idea of consent. While it is often presented as a direct question of “yes” or “no,” she reminds us that consent is embedded in cultural and social assumptions and contexts. From violence and consent on to questions of form: where is sexual violence in institutions visible and how do we understand it? Mahima Kaul challenged distinctions between online and offline forms of violence in an increasingly interconnected world.

The next block of blogs entered institutional life to ask what tussles and challenges emerge when sexual harassment and sexual violence are taken up here. From Australia, Jan Breckenridge traced a brief history of work on this issue raising the question of who is regarded as susceptible to such violence; Breckenridge’s piece importantly centers both staff and student experiences. Given the important changes that Breckenridge writes about, why does it seem as though so little progress has been made in addressing sexual violence in HEIs? Allison Henry stays with Australia to show that legislative and regulatory levers need not only to exist: they need to be activated, and she gives us examples of how this has happened. Angela Griffin turns to institutions from a student’s perspective exploring how they are perceived and drawing on her research to indicate what needs to change.

Representatives from #MeTooEdiUni, Amy Life and Sharessa Naidoo, take up this question from the context of the UK, showing how their active campaign allowed them the proverbial “seat at the table” where they felt they were being allowed to speak without actually being listened to. Bill Flack, our next blogger, offered some insights into why this might be so, showing that administrators and researchers need to always catch up with changing sexual cultures. “Some of the major challenges in this work are trying to ask the right questions in the right ways, being as inclusive as possible with regard to those groups who are targets of harassment and violence and to the types and contexts of harassment and violence, and the lack of support for – and often backlash to – doing this work,” Flack said.

Our final set of blogs show the challenges of addressing sexual harassment and sexual violence in higher education institutions. From Germany, Wendy Stollberg elaborated on the (im)possibilities of feminist institutional change, focusing on the figure of the Gender Equality Officer in Germany who might be highly motivated to address questions of violence but also to find themselves structurally constrained.

What are some of the structural constraints to institutional change in India? Our next blog outlined concerns related to the current functioning of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 (PoSH-Act). Perhaps the change needs to be effected in concert with wider institutional changes: Lora Prabhu showed how her NGO’s efforts in encouraging gendered participation in sports shifted how young women approach public and institutional spaces. From the University of Hyderabad context, Aparna Rayaprol wrote about the successes of student-led sensitisation efforts on campus. These efforts might be in-person, but students have also turned to online platforms as Adrija Dey writes, indicating their lack of faith in the “due process” of law that did not fulfil students’ ideas and imaginations of justice. Given the wealth of experience, knowledge, and research in these posts, where do we go from here? We end with an important reminder: activism on sexual violence in higher education institutions requires a different temporality and horizon. Anna Bull from the 1752 group writes crucially about “slow activism” that creates space to name the existence of a problem.

The 2023 curators:

University of Edinburgh: Dr Hemangini Gupta (Assoc Director and 2023 Blogathon Co-Lead), Prof. Fiona Mackay (GENDER.ED Governance Lead and 2023 Blogathon Co-Lead) and Rhea Gandhi (PhD web and editorial assistant) from GENDER.ED.

Dr B R Ambedkar University Delhi: Prof. Rukmini Sen, Dr Rachna Mehra.

University of New South Wales: Prof. Jan Breckenridge (Co-Convenor), Mailin Suchting (Manager) and Georgia Lyons (Research Assistant) for the Gendered Violence Research Network.

Guest curators: Dr. Heike Pantelmann (Managing Director) and Dr. Sabina García Peter (Associate), Margherita von Brentano Center at Freie Universität Berlin, for the Una Europa Gender Equality Network (UGEN).