Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) have become topics of global focus. From #Metoo to landmark judgements in international criminal justice processes, visibility – amid promising calls for action toward justice – is often contingent on the testimony of survivors. In our haste to hear these stories, the long-term impact of demands for testimony is overlooked.

In this post, I propose an alternative site in which we might listen to and hear testimony. Specifically, I take a look at arpilleras – appliquéd wall-hangings – from Peru, featured in the Conflict Textiles collection. The term ‘arpillera’ literally means burlap or hessian, the material on which the textile is made. However, the term has become synonymous with this form of appliquéd wall-hanging.

The Conflict Textiles Collection: From Chile to Peru

The Conflict Textiles collection is a physical and online archive of materials hosted by CAIN (Conflict Archive on the Internet) at Ulster University. Curated by Roberta Bacic and Breege Doherty, the mainstay of the collection is the Chilean arpilleras which were crafted to denounce violence under the Pinochet dictatorship. Made with the support of the Vicariate of Solidarity, arpilleras depicted the killing, disappearance, and poverty experienced under the regime, as well as acts of protest and everyday strategies of survival.

As with the collection itself, the arpillera travelled to other global contexts. Inspired by the Chilean arpilleristas (those who make arpilleras), women living through the Peruvian civil war (1980 to 2000) began to stitch the violence in their own country.

Curator Roberta Bacic uses the term “textile photograph” to describe the arpilleras; a reference to the way that they bear witness. The Peruvian arpilleras, like the Chilean pieces, testify to conflict experiences, depicting scenes of massacre, displacement and poverty, and commenting on issues related to gender-based violence.

‘Debo ser humilde y sumisa? / Should I be submissive and subservient?’, Peruvian arpillera, Anonymous, 1986, Photo: Martin Melaugh, © Conflict Textiles.

‘Debo ser humilde y sumisa?’ (Should I be submissive and subservient?) was produced in 1986 in Lima. The textile shows a gathering in a room which has two posters emblazoned on the wall. One states: “Women, value yourself!”, while the other rhetorically asks, “Should I be humble and submissive?”.

This is an emotive piece, with the figures stitched with a range of expressions: some cast their eyes and heads down, though others take a different stance: the figure in light blue appears inquisitive, while three women sat at the bottom of the textile hold a book, perhaps engaging with the themes in the posters. Above all, the arpillera depicts: ‘women who have already made a space to deal with their issues’.

Providing answer to the poster’s question, the arpillera emphatically portrays a space of agency, with suggestion of their ongoing discussion of issues related to gender, violence, and patriarchy.

‘

‘

Violar es un Crimen / Rape is a Crime’, Peruvian arpillera, MH, Mujeres Creativas workshop, 2008, Photo: Martin Melaugh, © Conflict Textiles.

‘Violar es un Crimen’ (Rape is a Crime) is a 2008 replica, with the original a design from the Mujeres Creativas workshops in 1985. The textile shows a protest which took place outside military command in Lima. On the right-hand side, a woman has entered the military command, angrily confronting the armed military police. All the figures wear dark colours and hold flowers, representing the cantata (the national flower of Peru). This flower is primarily found in the Andean mountains and its inclusion symbolises a connection to Ayacucho, the community for whom they protest.

Speaking about the arpillera, Maria (a participant of the action) states:

In October 1985 many people were killed in Ayacucho and women were raped, but nobody protested. Two groups of us decided to demonstrate in front of Comando Conjunto… since the people… living in Ayacucho felt too vulnerable to do so… [Later we] decided to make an arpillera of our action to show that we do not condone such brutality.

‘Rape is a Crime’ denounces sexual violence and displacement in Ayacucho through its depiction of resistance and solidarity with those unable to make their voices heard.

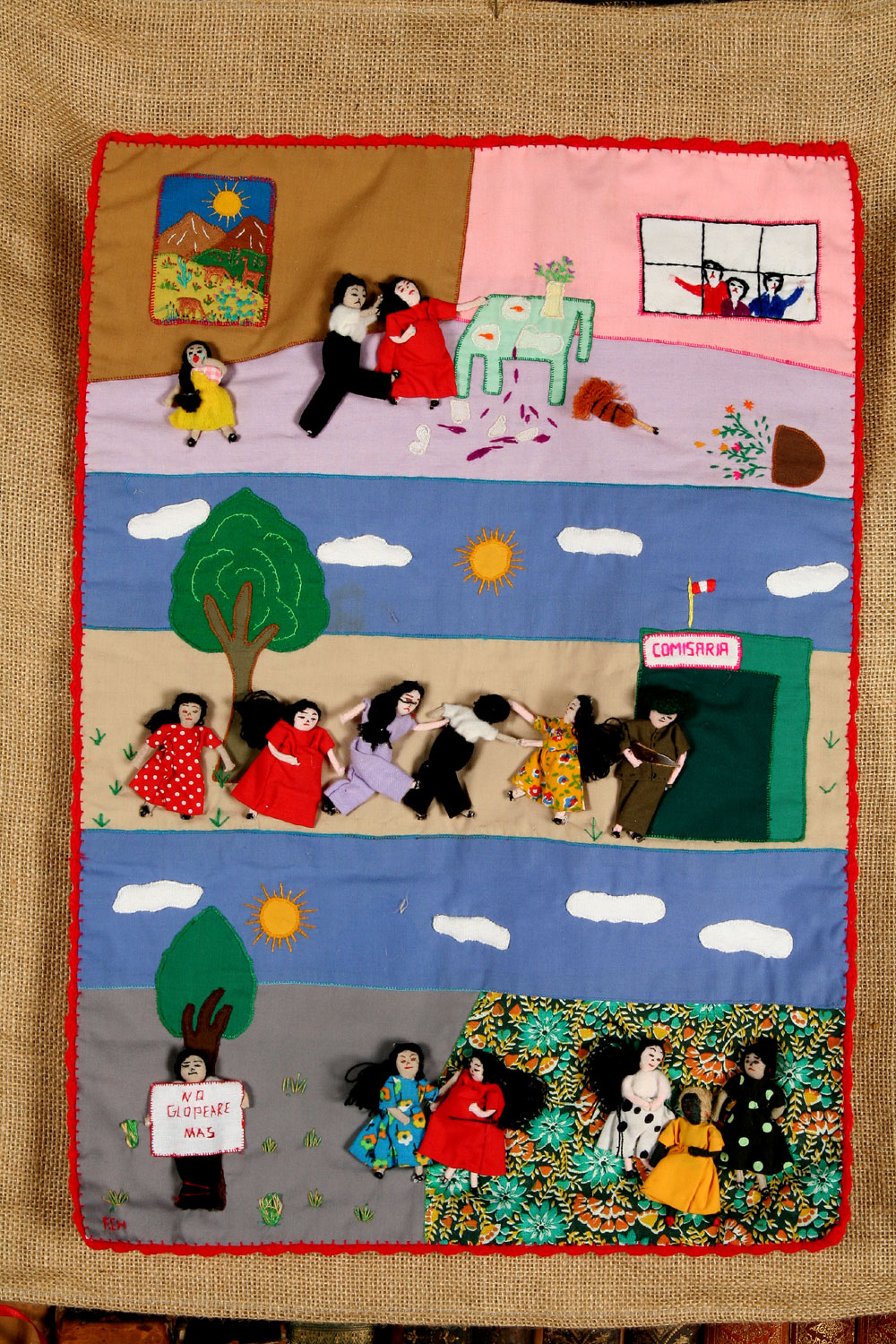

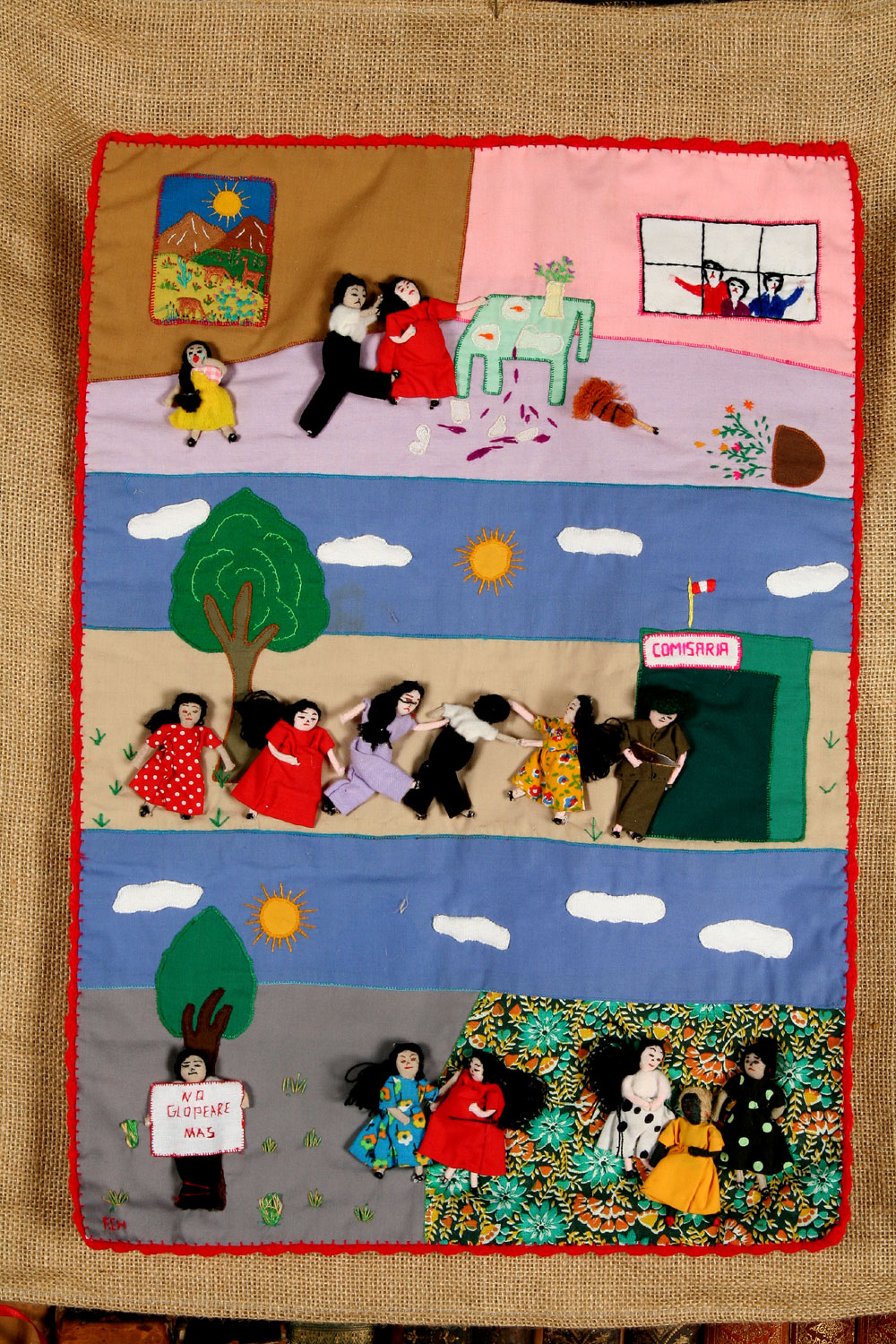

‘Violencia Doméstica / Domestic Violence’, Peruvian arpillera, MH, Mujeres Creativas Workshop, 2008, Photo: Colin Peck, © Conflict Textiles.

‘Violencia Doméstica’ (Domestic Violence) is another arpillera produced in the Mujeres Creativas workshops and responds to the contemporary context. The piece is divided into three sections. In the first, we are shown a scene of domestic violence within the home. The second shows the neighbours seeking justice at the local police station. Later, with the police unwilling to take further action, members of the community decide to enact their own justice. In the final panel, the man is tied to a tree and holds a sign which reads “I will not beat again”.

Responding to the prevalence of domestic violence in Peru, the arpillera again speaks to a wider discussion among the group on issues of gender-based violence, and signals toward community action toward justice.

Conflict Textiles are therefore a promising site to learn (and unlearn) our ways of knowing SGBV. Untangling narratives of victimhood, together the arpilleras stitch a continuum of gender-based violence. As textile testimonies to a range of gender-based violence, arpilleras bring women’s voices, agency, solidarity and resistance to the fore.

Dr Lydia Cole (@LydiaCCole) is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Durham University on ‘The Art of Peace: Interrogating community devised arts-based peacebuilding’. Completing her doctoral research at Aberystwyth University in 2018, her research engages at the intersections of feminist international relations theory, critical peace and conflict studies, and visual, creative and participatory research methods. Lydia’s research on gendered violence and conflict textiles has been published in journals including International Feminist Journal of Politics and Critical Military Studies. She has also co-curated exhibitions including Stitched Voices / Lleisiau wedi eu Pwytho and Threads, War and Conflict.