Picture above: Artwork above from the Everyday Heroes arts collaboration with students. Reproduced by permission

Ruth Friskney and Claire Houghton

Young survivors of gender-based violence are at the forefront of innovative responses to Gender Based Violence in Scotland. National young people’s participation projects like Voice Against Violence, Power Up Power Down, and Everyday Heroes have transformed Scotland’s understanding of gender based violence through young people’s perspectives. The projects’ creative, relationship-building approaches are rooted in the skills of support workers in empowering children to speak about abuse. Young survivors themselves innovate in speaking directly to people in power and reaching out to other children and young people experiencing GBV, including during Covid-19.

Young survivors have worked to see children and young people recognised as victim-survivors of all forms of gender-based violence. A Voice Against Violence film was used by young survivors to critique the lack of recognition of children in legislation about domestic abuse. A key step forward was achieved in the Domestic Abuse (Scotland) Act 2018 to finally recognise that the perpetrators’ ongoing psychological, physical, sexual and financial abuse adversely affects children as well as women.

Key messages are consistent across projects: young people don’t know how to seek support, support is inadequate, training is needed and specialist workers are invaluable. Young survivors have taken action on this, using fabulous innovative and creative methods: websites by young sexual violence survivors for support and information, training videos and resources like Super Listener for professionals and a national online platform currently being co-developed (That’s Not OK) to take forward survivor’s recommendations to Government.

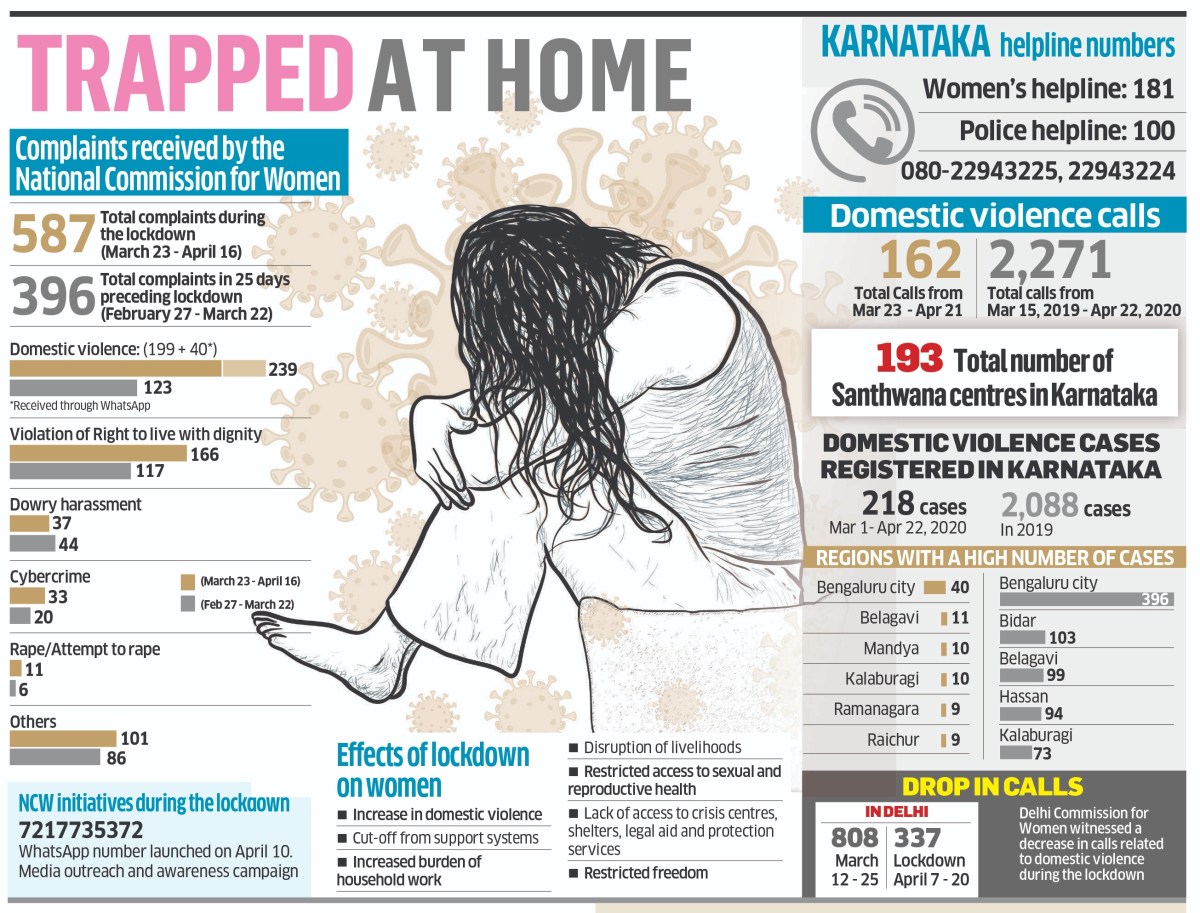

When COVID-19 hit, and evidence began to build about the ways in which the pandemic helped perpetrators of domestic abuse to harm women and children, Yello! a group of young advisers to Improving Justice in Child Contact (IJCC), felt that

we had to do at least something small to help out – or at least let someone out there know that they’re not alone and what they’re going through will pass. [1]

What it was like to make the animations, from Yello’s blog: We knew we had to help

Yello! wanted to make sure that children and young people knew that there was help and how they could get to it. They worked on two animations (“You are not alone” and “If home is not safe”) and supported partners across the five countries of IJCC to tailor animations for their own languages and contexts.

Locally, young experts from AWARE, Angus Women’s Aid’s Young Expert group, created their own film about what young people affected by domestic abuse might be feeling and the questions they would be asking during COVID. The film signposts sources of help, to make sure that young people affected by domestic abuse – in their own relationships or alongside their mother – know, even in COVID, that “You are not alone”.

A key message from all these projects is that the justice response to young survivors needs improvement – in particular for children and young people’s views to be given due weight and for the perpetrator, not the woman or child survivor, to be held accountable. Everyday Heroes’ call for action expressed through displays in Parliament and creative dialogue with key decision-makers resulted in a pledge for collaborative action by Ministers.

Child contact remains a key area of concern – one being considered by the Improving Justice in Child Contact project including Yello!, its young advisers. Evidence from young survivors indicates that domestic abuse continues even if a mother and child are able to separate from a perpetrator. Child[1] contact can be defined as communication, such as phone calls or spending time, with a parent that the child does not usually live with, and its type and frequency can often be set by the Courts. Child contact is often used by perpetrators to continue to harm mothers and children. COVID-19 has provided perpetrators with additional opportunities to enhance their abuse.[2]

“Don’t dismiss us – we experienced it, and we know what we’re talking about.”

From Yello!’s evidence to the Justice Committee

In Scotland, Yello! have been instrumental in the development of the Children (Scotland) Act 2020, meeting with the Minister, submitting written evidence, and taking part in person in a session with the Justice Committee. One young woman worked with Scottish Women’s Aid to write a case study of her experience of the child contact system – with the aim of giving decision-makers a glimpse of what it is like for a young person not to be listened to, and to be told to spend time with someone she feels unsafe with.

Internationally, IJCC have inspired partner organisations and the young people they work with to reach out creatively to share their experiences and to meet directly with people in power. For example, young people working with the IJCC partners in Portugal have been invited to meet directly with judiciary and other key stakeholders. Maria, a young person working with the IJCC partner in Romania, has written a blog, including poetry, about her experiences:

It was only one wish I have had,

I asked not to see him again

And it is such a sombre thing

You demand that I must visit him.

I read and a tear slipped my face

Because in danger you have put me

You told me I need to stay with him

As if it was a little thing.

Note to my judge

‘Maria’, 13 years old, working with the Romanian partner in the IJCC project, writing about the experience of reading the child contact court order

Young survivors of abuse have transformed policy and practice responses in Scotland through participation – and are inspiring young people internationally with what progress is possible. Such innovation needs resources and the support of competent adults to fully harness the wonderful power, talent, expertise and passion of young survivors.

“I think projects like ours are important because not that many children and young people have a say in their lives, because people think we are too young to know better.”

Yello!, on the experience of taking part in participation work

[1] There is a large academic literature on the impact of domestic abuse on children and the particular issues around child contact such as: Katz, E. (2016). Beyond the Physical Incident Model: How Children Living with Domestic Violence are Harmed by and Resist Regimes of Coercive Control. Child Abuse Review 25(1), 46–59. Callaghan, J., Alexander J., Sixsmith, J and Fellin, L. (2018). Beyond “Witnessing”: Children’s Experiences of Coercive Control in Domestic Violence and Abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(10), 1551–1581 Holt, S. (2017). Domestic Violence and the Paradox of Post-Separation Mothering. British Journal of Social Work 47 (7), 2049–2067; Mackay, K. (2018). The approach in Scotland to child contact disputes involving allegations of domestic abuse. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law 40(4), 477-495. Morrison, F, Tisdall, E.K.M., and Callaghan, J., (2020), Manipulation and Domestic Abuse in Contested Contact – Threats to Children’s Participation Rights. Family Court Review, 58 (2), 403-416.

[2] You can read Improving Justice in Child Contact’s response on COVID-19 to the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women

This blog was written by Dr Ruth Friskney and Dr Claire Houghton from the University of Edinburgh. Ruth is a Research Fellow on the Improving Justice in Child Contact project (funded through the European Union’s Rights, Equality and Citizenship Programme 2014-2020), working to improve participation in child contact processes for children affected by domestic abuse. Claire is a Lecturer in Social Policy and Qualitative Research working to improve young people’s impact on gender equality and gender-based violence policy, through Voice Against Violence (ESRC/Scottish Government funded), Everyday Heroes (Scottish Government) and the new ESRC UK project CAFADA. In writing this blog Claire and Ruth have drawn on the inspirational and creative work of the young people leading and taking part in the projects described in this blog, as well as the organisational partners: with thanks to them all.

Their twitter handle is @CYSRG1