Picture above: “Compassion through Computation: Fighting Algorithmic Bias.” Credits: World Economic Forum. Source: Creative Commons.

Zelda Solomon

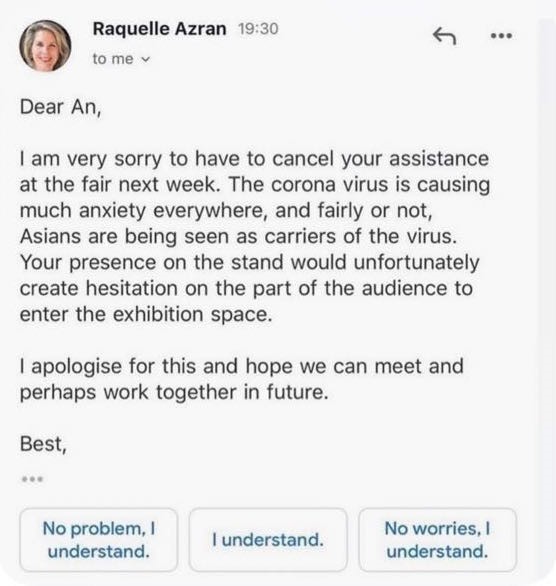

One of the first examples I saw of anti-Asian discrimination in response to corona-virus was that of An Nguyen, who is a Vietnamese curator that was due to exhibit an installation at the Affordable Arts Fair in Battersea, UK last March. In a screenshot of an email posted to her social media, dealer Raquelle Azran wrote to her:

“The corona virus is causing much anxiety everywhere, and fairly or not, Asians are being seen as carriers of the virus. Your presence on the stand would unfortunately create hesitation on the part of the audience to enter the exhibition space”

and cancelled Nguyen assistance at the event.

In her caption, An Nguyen wrote in response:

“It is the systematic structure of knowledge production that informs some of us that normalising non-aggressive discrimination is acceptable which needs to chang.e”

Re-reading these lines, I find myself turning to the suggested prompts.

The phrases “No Problem, I understand.” “I understand.” “No worries, I understand” are written in inoffensive blue, padding the screen in discreet boxes. These are the outputs of an algorithm that likely recognised the phrases “sorry” and “cancel” in Azran’s email and generated the pre-written responses. I didn’t notice them on my first reading, which I assumed was due to my eclipsing outrage and identification with Nguyen. However, technology’s ability to evade suspicion is partly by design; input technologies like predictive text are built to optimise user efficiency, marketed as objective, neutral tools that serve only productivity. We are not meant to see any motive or meaning in them.

In the bygone age of digital utopianism, Nguyen’s predictive text might be excused as a simple glitch. However, as theorists such as Ruha Benjamin and Saifya Noble have made clear, encoded bias is part of a larger, and growing, industry of control.

One case study Benjamin references in her book “Race After Technology,” (2019) explores the racial weighting behind selective encoding, citing how Google Maps read the name “Malcom X Boulevard” as “Malcom 10 Boulevard.” She explains how from an industry perspective, the translation of roman numerals is a feat, revealing the racial biases behind technological ideals of progress. As Benjamin writes, the glitch is not an “aberration, but a form of evidence illuminating underlying flaws in a corrupted system.”

Women of colour are often found in the intersections of oppression in the new digital world.

Saifya Noble

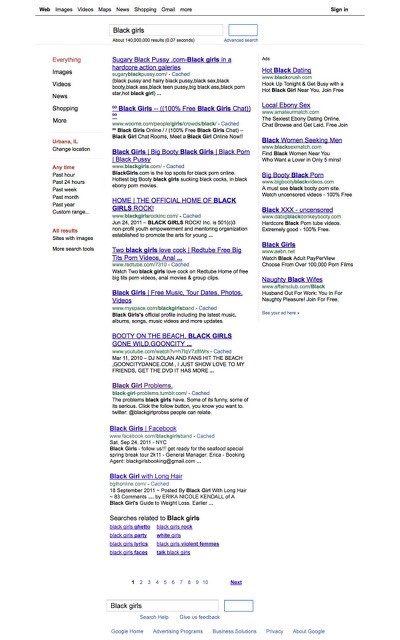

Noble opens her text “Algorithms of Oppression” (2018) with a Google search experiment she conducted in 2014, where she found the search terms “Black girls” “Latina girls” and “Asian girls” resulted in pornography pages, while then same is not found when searching “white girls”. Noble outlines that the prioritisation of racist and sexist content when searching for women of colour is not solely reflective of user-desire, but a product of bias engineering masquerading as objective coding.

The fact Nguyen’s device could interpret something as complex as human interaction but failed to recognise racism reveals what is categorised as valuable information. Nguyen’s exclusion is thus two-fold; the first at the hands of a gallerist who deemed her Asianness threatening, and the second at the hands of an algorithm that failed to recognise it.

As Jennifer M. Piscopo eloquently outlined in last year’s blogathon, we are witnessing an age where women, and more-so women of colour, are receiving an onslaught of abuse online to the extent it is re-shaping what it means to be a woman in public life. Theorists such as Benjamin and Noble are building on this research, looking to the encoded systems that facilitate and reproduce oppression online. They encourage us to approach advancing technology with a critical eye, and refuse to greet the sexist or racist glitch with the predicted : “No problem, I understand.”

References

Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race after Technology : Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Newark: Polity Press.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. 2018. Algorithms of Oppression : How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: New York University Press.

Zelda Solomon is a 4th year History of Art student at Edinburgh University. She is on the Edinburgh College of Art Board for decolonising the curriculum and was previously the Black and Minority Ethnic Liberation Officer for Edinburgh University Students Association (EUSA). She co-founded the SexyAsiansInUrArea theatre company that recently released a short film on preforming Asian identity for RUMAH festival. She is currently focusing on how race is represented in the digital age.

You can follow her on Instagram @zeldasolo