Featured image source and in-text images: Website of Partners for Law in Development

Partners for Law in Development (PLD)

It’s been a decade since India’s premier law governing sexual harassment at work, the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 (PoSH-Act) came into effect. Today, the law makes news mostly in the context of high-profile cases and broader social movements like the #MeToo movement. The absence of a formal monitoring and review process, and availability of public data has rarely been the focus of public attention and debate, but is of serious concern. Partners for Law in Development (PLD), a legal resource group, has systematically documented observations through its work on building capacities with government and higher education institutions. We have examined how the law functions under the PoSH-Act and outlined the protection gaps in order to contribute towards building knowledge and the discourse on the subject. Although not an exhaustive list, these are the concerns that relate to the functioning of the law that appear to cut across sectors and deserve attention.

I. Compliance largely limited to the creation of Internal Committee:

Workplaces often prioritise the formation of Internal Committees (IC) to demonstrate compliance with the law. However, it’s common to establish ICs only after a complaint of sexual harassment at the workplace. Delays in appointing ICs and long gaps between the appointments of new members have been observed within the first five years of the law’s implementation. This emphasis on IC creation may give the misleading impression that a workplace is free of sexual harassment. Unfortunately, training and orientation sessions are often neglected, held briefly, or treated as one-time events. Furthermore, government departments and agencies encounter challenges in organising meetings due to officials’ busy schedules. Many employees, including senior staff, are often unfamiliar with their workplace’s sexual harassment policies.

While many ICs exist, they may be inactive, lack functioning email addresses, or consist of unaware committee members. A similar situation is observed with Local Committees (LC), which are often unappointed or non-functional. Despite the existence of penalties for non-compliance, the lack of monitoring renders these penalties ineffective.

II. Insufficient training and sensitisation for the Committee:

Insufficient training and sensitisation result in uninformed committee members who lack the necessary skills to handle sensitive cases. Maintaining confidentiality is challenging, and committee members are often unclear about their responsibilities and the law’s requirements. Confusion often arises regarding disclosure of complaint content, regularity of IC meetings, the committee’s role in preventive work, the committee’s mandate to provide recommendations, interaction between parties involved in a complaint, and whether an unsuccessful case of sexual harassment constitutes a false claim. In some cases, external members’ roles are rendered ineffective, as they may not be included in inquiries, receive short notice, or lack impartiality.

III. Challenges in relation to new and emerging workspaces:

The law does not provide guidelines for adapting it to new and emerging workplace types, such as shared workspaces, where individuals or groups rent communal workspace by the hour or day. Workers in the unorganised or informal sector often struggle to access the law, given the requirement to go to district headquarters to file complaints and participate in inquiries, resulting in lost wages. Unorganised sector workers and new workplace models do not align with the IC structure outlined in the law. Challenges also arise in addressing complaints against third parties in the organised sector when there is no financial contractual relationship with the organisation. Although Local Committees may be an alternative, they often do not exist or remain non-functional, creating a gap in the law. Even when they function, LCs lack the means to compel respondent participation or enforce their directions.

IV. Efficiency versus transformatory approaches:

Efficiency often takes precedence over holistic redressal, with organisations adopting approaches like the ‘zero-tolerance’ model, which results in termination for any harassment transgressions. However, this approach may lead to disproportionate punishments for minor wrongs that could be addressed through counselling, apologies, or other approaches as recommended by the law. It also avoids investing in transformation and problem-solving. Other shortcuts to inquiry include respondents resigning upon notification of a complaint, complainants facing retaliation, and workplace cultures that prioritise efficiency and profit over social responsibility.

V. Local Committee and the Informal Sector

Local Committees are intended to serve women workers in the unorganised sector, including domestic workers, cases where ICs do not exist, and cases against employers. However, LCs face delays, a lack of information, and inadequate training. Their role in relation to the unorganised sector, particularly domestic workers, is largely notional, as they can only refer matters to the police for inquiry and action. Accessing remedies is unrealistic and onerous for domestic workers in the absence of support services, workers’ unions, job security, and the need to travel long distances.

Conclusion

The above findings have emerged from extensive trainings carried out by PLD, which formed the basis for documenting the types of cases commonly reported, frequently asked questions and the gaps in statutory law. The full report of the findings can be assessed here.

Author bio

Partners for Law in Development (PLD), established in 1998 as a legal resource group works towards realising social justice and women’s rights. PLD carries out evidence based research studies, produces legal explainers on laws, posters for raising awareness on gender justice for women, and among other things engages actively with diverse stakeholders. Since the enactment of the PoSH-Act in 2013, PLD has conducted more than 160 trainings and workshops till 2019, covering more than 7300 participants from about 17 states. The findings emerging from these trainings have informed the current research paper.

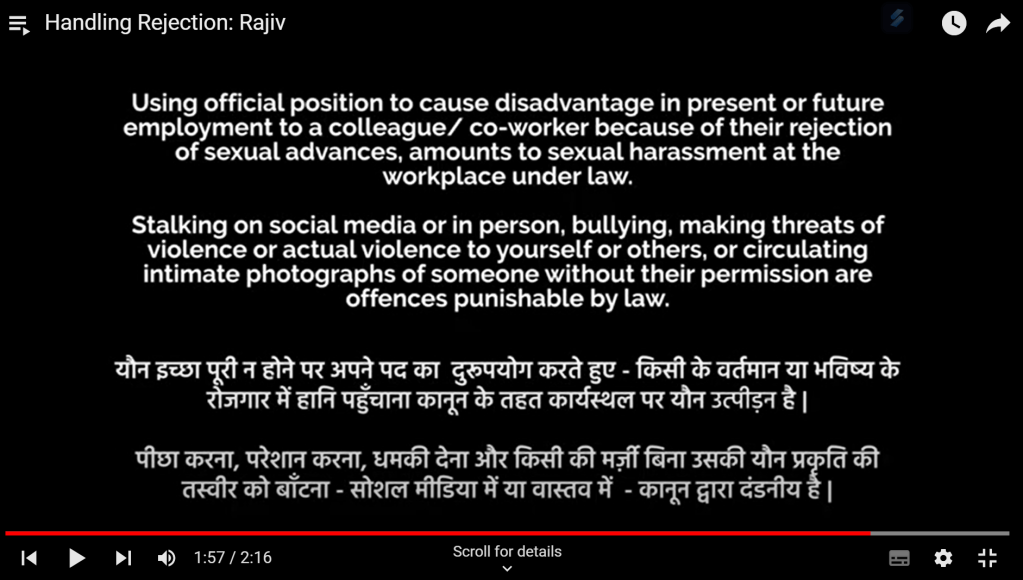

Additional Media Learning

This is a series of 11 short videos on consent and rejection – conversation starters to nuance framing consent beyond binaries of victim-perpetrator, or yes-no, developed from real stories that emerged through the sexual harassment prevention work carried out by Partners for Law in Development, the video-series encourages critical, self-aware expressions of intimacy and the related grey areas of boundary setting, peer pressure, stereotyping that shape our conduct and assumptions. This series seeks to go beyond crime and punishment to explore and encourage conversations leading to transformatory approaches to popular attitudes and assumptions about sexuality.