Ngozi Anyadike-Danes

Sexual consent is commonly presented as the defining concept of sexual violence and, thus, often seen as the differentiating factor between consensual and non-consensual sexual activity

(Munro, 2008).

Yet, what sexual consent means and how this meaning is applied appears to result in some degree of discord, particularly in the context of university based sexual violence.

Sexual consent is best understood as an agreement between those wishing to engage in sexual activity. Each core concept is associated with some conditions:

- The agreement must be informed, freely given and can be taken back at any time.

- Each person must agree and have the capacity to agree (e.g., be of legal age, not excessively intoxicated) and understand what they’re agreeing to.

- The sexual activity is specific to the sexual act.

Stripped back, sexual consent is relatively straightforward. But definitions of sexual consent merely highlight construct and conceptual structure, they lack the context of culture and society. When we consider students, for example, research suggests that their sexual consent definitions, generally, accord with the above (Wignall et al., 2022; Brady et al., 2018) – an agreement to engage in sexual activity with some awareness of factors that might mitigate consent (e.g., age, intoxication, coercion). Similar results were identified during my PhD research (Anyadike-Danes, 2023) when university students were asked to define sexual consent (Figure 1). Yet, consent definitions, understanding and behaviour are not necessarily the same (Beres, 2014; Marg, 2020).

Sexual consent understanding supplements definitions with contextual information like societal norms, cultural attitudes, and adherence to religious beliefs (Muehlenhard et al., 2016). This could mean that there are situations where students think sexual consent is not necessary (e.g., married, certain sexual acts). Though research seems to suggest that certain gendered and victim-blaming beliefs are reducing in students (Yapp & Quayle, 2018), students’ responses may also reflect their awareness of social desirability and suggest that our measures require updating (Zidenberg et al., 2022).

Figure 1. Word cloud of university students’ sexual consent definitions.

Sexual consent understanding also influences how individuals communicate consent – whether that’s their communication to/with someone, or their interpretation of someone else’s consent communication. Affirmative consent (Friedman & Valenti, 2019), or ‘yes means yes, no means no’, means that anything other than a ‘yes’ (often a verbal ‘yes’) is non-consent. The verbal ‘yes’ has been heralded as the ‘gold-standard’ of consent communication because it limits the risk of miscommunication (Beres, 2014). Yet, putting such expectation on the word ‘yes’ means that other cues that refute that ‘yes’ might be missed. For example, if someone consents after having said ‘no’ several times throughout the night, is that consent?

Figure 2. Awareness raising campaign from Geelong (Australia) Sexual Assault & Family Violence Centre.

Figure 2 features a campaign message from an Australian support centre that highlights the reality that ‘no’ may not always be literal, it can take different forms. Just like we understand that ‘yes’ can be non-verbal, so too can be said for ‘no’. From research, studies suggest that students may understand the importance of verbal communication, but that is not how they communicate (Muehlenhard et al., 2016). Rather, they prefer non-verbal or more implicit means of communication (Jozkowski & Peterson, 2014). And, expectedly, this introduces a greater likelihood of miscommunication. If we expand sexual consent beyond a binary conceptualization and view it as a spectrum – yes, no, and somewhere in between – then we should also reimagine communication the same way: verbal, non-verbal and nothing at all. Especially as we consider what drives whether someone consents (or not).

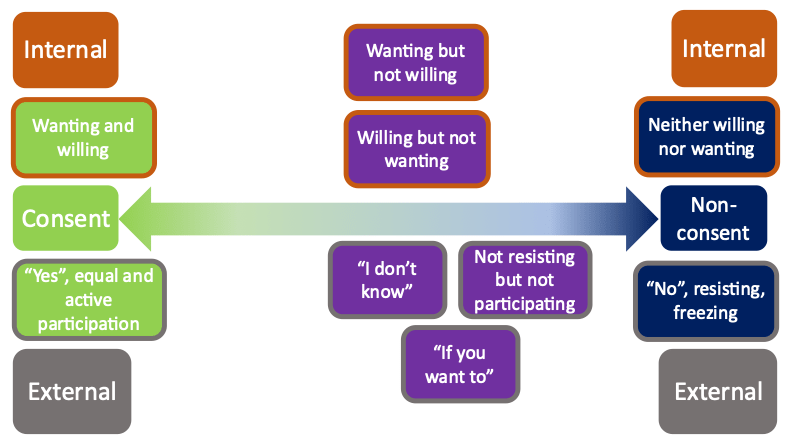

Figure 3. Visualizing sexual consent as a spectrum.

To some, sexual consent is an internally motivated desire or willingness to engage in sexual activity. This is more in keeping with when someone is asked how they knew someone wanted to have sex and they say that “you just know” (Wignall et al., 2022; Willis & Jozkowski, 2019). In research terms, this is known as ‘tacit knowing’ (Beres, 2010). Rather than solely an external or internal manifestation, sexual consent is more than likely a blend of both. Figure 3 seeks to visualize different consent concepts and behaviours across that spectrum.

But how does this all relate to gender-based violence?

Research suggests that secondary school students do not receive sufficient education on sexual consent and what that means for their relationships

(Pound et al., 2016; Setty, 2023).

Understanding sexual consent is just as much about learning definitions as it is about empowering young people to know their boundaries and feel confident voicing what they like and what they do not like. Not only might this education impact the prevalence of gender-based violence but it may also provide those victimized with the language to report their experiences (Rousseau et al., 2020). Conceptualizing sexual consent as yes or no may be a catchy slogan but it is merely a conversation starter – we must follow up these catchphrases with in-depth learning discussions about the breadth of sexual consent and what that means for relationships.

The importance of sexual consent cannot be overstated: it determines whether a sexual act is criminal. But in reality, it can mean so much more.

REFERENCES

Anyadike-Danes, N. (2023). Sexual consent within unwanted/non-consensual sexual experiences: exploring definitions, understanding and impact amongst university students in Northern Ireland [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Ulster University.

Beres, M. (2010). Sexual miscommunication? Untangling assumptions about sexual communication between casual sex partners. Culture, health & sexuality, 12(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050903075226

Beres, M. A. (2014). Rethinking the concept of consent for anti-sexual violence activism and education. Feminism & Psychology, 24(3), 373-389. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353514539652

Brady, G., Lowe, P., Brown, G., Osmond, J., & Newman, M. (2018). ‘All in all it is just a judgement call’: issues surrounding sexual consent in young people’s heterosexual encounters. Journal of Youth Studies, 21(1), 35-50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2017.1343461.

Friedman, J. & Valenti, J. (2019). Yes means yes! Visions of female sexual power and a world without rape. Seal Press.

Jozkowski, K. N., & Peterson, Z. D. (2014). Assessing the validity and reliability of the perceptions of the consent to sex scale. The Journal of Sex Research, 51(6), 632-645. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.757282

Marg, L. Z. (2020). College men’s conceptualization of sexual consent at a large, racially/ethnically diverse Southern California University. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 15(3), 371-408. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2020.1737291

Muehlenhard, C. L., Humphreys, T. P., Jozkowski, K. N., & Peterson, Z. D. (2016). The complexities of sexual consent among college students: A conceptual and empirical review. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(4-5), 457-487. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1146651

Munro, V. E. (2008). Constructing consent: Legislating freedom and legitimating constraint in the expression of sexual autonomy. Akron L. Rev., 41(4), 923-955. https://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol41/iss4/5

Pound, P., Langford, R., & Campbell, R. (2016). What do young people think about their school-based sex and relationship education? A qualitative synthesis of young people’s views and experiences. BMJ open, 6(9), e011329. https://doi.org/ 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011329

Rousseau, C., Bergeron, M., & Ricci, S. (2020). A metasynthesis of qualitative studies on girls’ and women’s labeling of sexual violence. Aggression and violent behavior, 52, 1359-1789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101395

Selwyn, N., & Powell, E. (2007). Sex and relationships education in schools: the views and experiences of young people. Health Education, 107(2), 219-231. https://doi.org/10.1108/09654280710731575

Setty, E. (2023). Co-designing guidance for Relationships and Sex Education to ‘transform school cultures’ with young people in England. Pastoral Care in Education, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2023.2228804

Wignall, L., Stirling, J., & Scoats, R. (2022). UK university students’ perceptions and negotiations of sexual consent. Psychology & Sexuality, 13(3), 474-486. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2020.1859601

Willis, M., & Jozkowski, K. N. (2019). Sexual precedent’s effect on sexual consent communication. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(6), 1723-1734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1348-7

Yapp, E. J., & Quayle, E. (2018). A systematic review of the association between rape myth acceptance and male-on-female sexual violence. Aggression and violent behavior, 41, 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2018.05.002

Zidenberg, A. M., Wielinga, F., Sparks, B., Margeotes, K., & Harkins, L. (2022). Lost in translation: A quantitative and qualitative comparison of rape myth acceptance. Psychology, Crime & Law, 28(2), 179-197. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2021.1905810

AUTHOR BIO

Ngozi Anyadike-Danes is a postdoctoral researcher within Ulster University’s School of Psychology. Currently, she’s working on a Shared Island Initiative funded project: Consent, Sexual Violence, Harassment and Equality in Higher Education (COSHARE). This project aims to produce an all-island strategy in response to consent, sexual violence and harassment (C-SVH) in HE and facilitate knowledge exchange between academics and professionals (COSHARE Network). In January 2024, Ngozi will begin a lectureship within Ulster University’s Criminology and Criminal Justice program. Ngozi’s research interests concern sexual consent knowledge and understanding, unwanted/non-consensual sexual experiences, rape myth acceptance and designing measurement tools that explore sexual victimization.

Contact e-mail: n.anyadike-danes1@ulster.ac.uk