Sinéad Kennedy

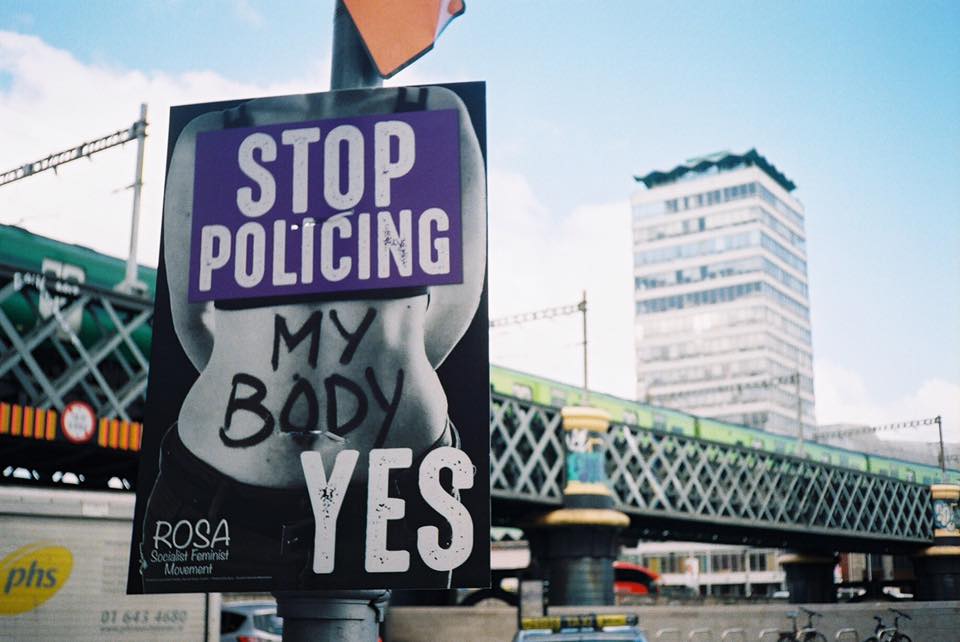

Featured image: ‘Stop Policing My Body in Dublin’, taken by Aerin Lai

In almost all European countries abortion is permitted. According to the Centre for Reproductive Rights, standard European practice is to legalise abortion on request or broad social grounds, in at least the first trimester of pregnancy. In addition, most countries also ensure that abortion is legal throughout pregnancy when necessary to protect the health or life of the woman or pregnant people. Only in a very small minority of European countries, namely Poland and Malta, does the law prohibit abortion in almost all circumstances.

Yet, abortion provision remains subject to criminal law: abortion services may largely be provided as part of maternal and reproductive health, but unlike other aspects of healthcare, abortion continues to be conceptualised within a legal framework.

So instead of the law guaranteeing the right to abortion, abortion is understood as a criminal offence – either by the person seeking the abortion and/or the medical practitioner providing the service – and therefore only permitted within a legally controlled framework.

The consequences of violating this framework include hefty prison sentences. No other form of healthcare is subject to this level of criminalisation and it creates a profound “chilling effect” on both those seeking abortion care and on healthcare providers offering legal abortion services.

Even in countries where legal restrictions may only apply to the stage at which abortion is available, criminalisation still results in a precarious social and legal situation for people in need of abortion, forcing many to travel to access the services that they need. This system of “enforced” mobility disproportionality effects those with neither the means nor the ability to be “mobile”, particularly poor women, disabled women, migrant women and pregnant people.

Abortion access, therefore, is intimately connected with questions of mobility and immobility. Mobility allows some people to move and requires other people to remain fixed in place. Thus the term “mobility” captures both movement and “stuckness,” meaning the ways in which movement occurs, and the attempts to regulate or prevent it.

Reproductive mobility is used by states to regulate and discipline the act of reproduction. Particularly as embodied in women’s fertility; it becomes a means of fixing fertility: dealing with, sorting out, and putting it right.

Reproductive mobility is a contested space; a site of conflict but also a site of potential political transformation. Indeed the issue of reproductive mobility has become a key aspect of abortion activism. For example in Ireland, where abortion was criminalised in almost all circumstances except where a woman’s life was at risk, abortion activists have long exploited the political potentialities inherent in reproductive mobility, underscoring the hypocrisies and vulnerabilities inherent in the Irish state’s regulation and control women’s fertility and mobility. During the successful 2018 “Repeal” campaign to legalise abortion, activists highlighted how Irish women have long sought to access abortion through mobility.

For decades in Ireland, abortion was shrouded in secrecy and shame. Then, in 2013, the story of the death of Savita Halappanavar because an international story that exposed the violence behind Ireland’s criminalisation of abortion. Savita, a 31 year-old Indian national living in Ireland, attended a leading Irish maternity hospital, miscarrying for 16 weeks. Doctors there felt unable to offer standard medical treatment due to the presence of a foetal heartbeat. Pleading for her life, Savita repeatedly asked for an abortion but was refused and was told “Ireland is a Catholic country”. Five days later she died of septicaemia.

The Irish campaign to legalise abortion that exploded in months after Savita’s death saw the historic silence around abortion evaporate as thousands of women came forward to tell their abortion exile stories publicly through campaign groups like TFMR (Termination for Medical Reasons) and anonymously through the In her Shoes campaign.

These stories included the experiences of women who have been raped; women who were denied life-saving medical treatment like chemotherapy simply because they were pregnant; women with desperately wanted pregnancies, who after receiving the devastating diagnosis of a fatal-foetal anomaly were told they must continue their pregnancies to term regardless of the outcome.

Criminalising abortion did not stop Irish women from ending their pregnancies; If they were “mobile”, they travelled to Britain to access abortion. If they were “immobile” they risked a 12 year prison sentence and sought clandestine, illegal abortions even if that meant putting their lives, health and liberty at risk.

Most importantly, these abortion stories themselves also “travelled” between national contexts, becoming a key focus for activists in Malta, in Poland and in United States. These stories highlighted the enforced immobility of many women within borders, especially asylum seekers who remain “stuck” and unable to access abortion because they lack mobility. This political form of storytelling not only humanises women and pregnant experiences, but also exposes how a state’s control and criminalisation of reproductive healthcare amounts to nothing less than state-sanctioned gender-based violence.

Author’s Bio

Sinéad Kennedy teaches in the Department of English at Maynooth University, Ireland. She was a founding member of Together for Yes, the 2018 campaign to remove Ireland’s constitution ban on abortion and continues to campaign for reproductive justice in Ireland through Action for Choice.